The organ is a wind instrument—and a reed—and a percussion—and sometimes electronic—sometimes all at the same time. The organ has a deep history. It goes back to ancient Greece. Many variations were developed over the centuries, but essentially organs are comprised of a set of pipes of varying lengths, each producing a note as air is pushed through it. They can be small and portable, like an accordion (a reed organ), or so large they take many chambers to house all the various pipes and mechanics. In the Middle Ages organs grew larger to fill the space of a Gothic church with impressive, ominous sound. More recently, the theater organ was built to accompany silent films. These were given lots of percussion and a slew of other kitschy instruments for sound effects. The symphonic organ, the biggest and baddest of ’em all, has a more pedigreed background. Created to imitate, in a sense, a symphony orchestra, they provide a wider spectrum of musical sounds and greater dynamics to enable the organ to be more expressive. E. M. Skinner (1866-1960), the most prominent of symphonic organ builders, was renowned for his innovations, specifically for improving the mechanics and standardization of the console.

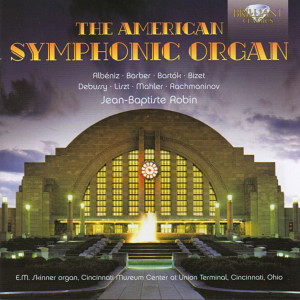

But an organ is also reliant on the space it’s been housed. Old churches, their stone construction, cavernous high ceilings and long nave, produce long reverberation times. That resonant characteristic is prized by organists and exploited by composers. The Skinner organ on this recording, most of it, was originally installed in Immaculate Conception Church of Philadelphia. The antiphonal, also Skinner, came from the private home of Powel Crosley, Jr. Today they are housed in a 1930s train station. Cincinnati’s Union Terminal, now repurposed into the Cincinnati Museum Center, is home to the Museum of Natural History & Science, the Cincinnati History Museum, Children’s Museum, and still has a couple of Amtrak trains running through it. The grand entrance to the terminal is noted for its intact art deco design, depression era murals, and the immense half dome covering the rotunda. This magnificent entrance is more than a visual wonderland. It is an acoustic wonderland boasting an equally immense reverberation time, about six seconds, more than some cathedrals. Organists are ecstatic when they play this organ. There is, however, a downside. A reverberation time this long presents special challenges for the performer. Complex music turns to mush. It’s been defended as a “great effect,” but as with any highly unique quality it can be overwrought, and descend into triviality.

Jean-Baptiste Robin doesn’t let himself or the music get derailed. He has carefully chosen compositions appropriate for the space. The recording is a delight from track one to the last trace of sound on the final track. It’s great music, expertly performed, and presented in a special acoustical environment. The CD opens with Debussy’s “La cathédrale engloutie.” The reverb acts like the sustain pedal on a piano, allowing Debussy’s lush harmonies to blend into mesmerizing invocations. Cut after cut shows off Robin’s technique, the organ, and the rotunda. Not only does he take advantage of the acoustics, he makes exceptional use of the organ’s capabilities. I’ve heard other recordings of this organ, and I’ve been present to a number of live performances there, most were disappointing. Robin is the exception. He gets more out of that organ than I’ve ever heard. He commands the organ’s wide dynamics and the full color range of its broad collection of divisions and ranks. There is one small exception, the Prelude in e minor by Rachmaninov, which highlights this organ’s limits. The prelude has a section of chords rapidly alternating between left and right hands. It may be an interesting effect to hear it played with six long seconds of reverb, but it’s a train wreck.

The recording is to be noted, too. The entire scope of the organ, from its lowest C, a 16 hertz gut-wrencher, to the full-on forte-fortissimo ringing throughout the dome, has been skillfully captured. This is a recording you have to be careful playing. Nothing has been held back, nothing throttled. You are advised to go easy especially on the Mahler. There is a low and loud pedal note in the left channel that caused my amp to clip and the subwoofers to hit their maximum excursion. This recording could damage your speakers if played at realistic levels. Be forewarned.

That brings us to the organ’s curator. Harley Piltingsrud is a knowledgable and dedicated organ enthusiast. He has put his heart and soul into the installation and restoration of this organ, almost single handedly. No doubt, the venue’s monumental acoustics have been part of his motivation. He is also the recording engineer. A retired physicist, he takes doing-it-right seriously. For practical reasons this recording is not true stereo. Several microphones were used, by necessity, to capture a realistic representation of what you’d have heard had you been sitting in the middle of the rotunda. A true two-microphone stereo recording would have sorely compromised the subjective experience. (Curious how our ears and psychoacoustic perception contrasts with how microphones collect sound.) And yet, the two-channel mix does provide a great sense of space and some inference to pipe location. Accurate or not, it’s aurally convincing. Listen to the results.

Debussy, La cathédrale engloutie

an original composition by Robin, Cercles Lointains (Distant Circles)

(||) Rating — Music : A- ║ Performance : A- ║ Recording : A ║ Jean-Baptiste Robin, The American Symphonic Organ, Brilliant Classics, 2013

![[art]by[odo]](https://artbyodo.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/cropped-Header.jpg)