Baroque music used to intrigue me. Classical used to entertain me. Romantic used to excite me. And to some degree they still do. But if I want to listen to something that twists my expectations into crusty knots, I need more than the counterpoint of Scarlatti, more than the saccharin of Corelli, more than bombast of Tchaikovsky. I need the some briny contemporary compositions that place demands on my ears.

Baroque music used to intrigue me. Classical used to entertain me. Romantic used to excite me. And to some degree they still do. But if I want to listen to something that twists my expectations into crusty knots, I need more than the counterpoint of Scarlatti, more than the saccharin of Corelli, more than bombast of Tchaikovsky. I need the some briny contemporary compositions that place demands on my ears.

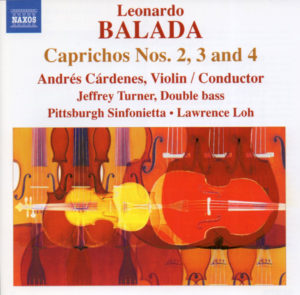

Leonardo does it. His name conjures a Renaissance artist from Vinci, however, this Leonardo is from Barcelona. He was born during Europe’s sour atmosphere still recovering from the first big one, and leading up to the second big one. It was a time of fermenting tensions. The music of the day reflected their anxiety. Dissonance and atonality rising from the Second Viennese School, lead by Schoenberg and his followers, Berg and Webern, took hold and spread internationally. It’s consequences continue to be felt. Barcelona’s Leonardo Balada may have been born in the throws of atonality, and his music may reveal some reminders of that era, he wasn’t bound by the past, or hindered by its closed minded rules. His dissonance is tempered, his tonality not lost. Although, it’s not always accurate to call it tonality in the conventional sense. It’s there. He teases us with it, then he snatches it away. He takes it the hinterlands of quasi-tonality, or perhaps more aptly, ambi-tonality. Bits, here and there, of “do” keep our ears trained on chewy bites of lye dipped themes—challenging, but not impossible—sometimes twice-baked to a crispy satisfaction. Listen—

.

.

.

Capricho #2, Jarabe

Capricho #2, Tango

Capricho #2 is a set of three dances, a samba, a tango, and a jarabe. The samba doesn’t feel all that danceable, but the basic samba rhythm is discernible, if you listen hard. Balada also refers to other popular forms in Caprichos 3 and 4. Number 4 is subtitled “Quasi Jazz.” Really? Jazz? Even quasi is questionable. There are tidbits of jazzish elements, but the rhythm is stilted, militaristic—not even close to the laid back ease and flowing drive of jazz. It’s embarrassing when academic composers and classically trained musicians make blundering attempts at jazz. Okay, it’s not supposed to be Jazz, but get real. When jazz musicians borrow from classical, they don’t call it quasi-classical. They don’t try to pretend it’s “classic.” They aren’t bragging about how sophisticated they are by co-opting classical phrases in their jazz. They take it as inspiration, play with it, bounce it around, make it their own. It’s fun—it’s creative. I never get pretense from jazz musicians’ borrowing, however, when “legit” musicians take popular music and try to mould it into “serious” styles, there’s something false about it. If only they’d cease making a point of, “Look at how giggywiddit I am. I’m putting jazz in my music.” Let listeners discover the borrowed influences on their own. Have a little respect that the audience can figure it out all by themselves. Play with the borrowed material, knead it, add seasonings to it, twist it into genuinely new shapes. Make it fun and creative. After that harangue, you might think I’m bashing Capricho #4—not at all. The music with its hint of popular influences is engaging, and possibly its saving grace. As for influences, jazz barely makes a ding. I hear Stravinsky, Coplan, Herrman (music for Psycho), and a little shot of the blues, more than I hear jazz.

The most tonal and creative Capricho on the CD is number 3. It’s titled “Homenaje a las Brigadas Internacionales” (Homage to the International Brigades), dedicated to the international volunteers who fought in the Spanish Civil War. Here folk tune references are unmistakable with no pointing it out. He takes these themes, contorts them with ambi- and poly-tonal novelty. He adds puckering dissonance to contrast with the savory tunes. Two of the five movements are slow, thoughtful pieces, suitably named, “In memoriam,” and “Lamento.” Each serving up mustardy bitterness against the salty tenderness of the folk melodies. All five are excellent examples of making creative fun. Listen—

Capricho #3, “Si me quieres escribir”

Capricho #3, “Lamento”

Capricho #3, “Jota”

Balada’s music reminds me of my first John Coltrane album. Initial listening left me thinking, “Eh, okay.” Next listening, “Yea, this is pretty good.” Another listening, “Wow. Now I’m getting it.” And each subsequent listening disclosed more of its piquancy. I’m finding these Caprichos doing the same. This is the sign of something better than good. Something lasting, something that will continue to fascinate. Something I’ll go back to for the familiar flavors and the crunchy fresh.

Balada’s music reminds me of my first John Coltrane album. Initial listening left me thinking, “Eh, okay.” Next listening, “Yea, this is pretty good.” Another listening, “Wow. Now I’m getting it.” And each subsequent listening disclosed more of its piquancy. I’m finding these Caprichos doing the same. This is the sign of something better than good. Something lasting, something that will continue to fascinate. Something I’ll go back to for the familiar flavors and the crunchy fresh.

.

(||) Rating — Music : A- ║ Performance : A ║ Recording : A ║ Leonardo Balada, Caprichos, Naxos, 2011

![[art]by[odo]](https://artbyodo.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/cropped-Header.jpg)