Few books get better as you read further into them. Most slump horribly in the middle, and some never recover from the slump. Biographies can be exceptionally tiring. Here’s an exception. A book about the life of Henry Wallace—a name that when mentioned has yet to fail to elicit a blank expression. It starts out rather slowly, plodding along, recounting Wallace’s childhood and youth, his father and grandfather, and his character shaping life in rural Iowa—the middle of the corn belt—the middle of the middle—middling squared. Drudge through the first couple of chapters, the background is necessary, and know that every succeeding chapter will build greater tension as it exposes the stratagems of midcentury American politics. But don’t expect this book to be a wild dramatization to juice up a mediocre life lolling down a cornfield lined backwoods road. There is no exaggeration, no pumping up dull moments with hyperbole. This is no hagiography. It shows him warts and all. His life story is unfolded in a matter of fact way that only makes the real life drama stand out with stinging presence.

Henry Wallace is a forgotten name. He’s been relegated to the freezer of history. It’s shocking when one realizes that he served as Secretary of Agriculture for eight years under Franklin Delano Roosevelt. His accomplishments in the fields of corn and chicken hybridization are still reaping benefits today. His political influence during the 1930s and early ’40s rippled through the country and around the world. It’s more shocking when one realizes that his name recognition and favorable polling numbers hit record highs yet to be broken by anyone in the national spotlight. It’s still more shocking that he was vice-president under FDR during the third term. He was the people’s number one choice for vice-president in 1944. Then to find out the shocks don’t stop there, that his prominence and popularity plummeted to record lows in a matter of months after being a shoe-in candidate, again, for the democratic presidential nomination in 1948.

The story of his rise and fall is the story of the American Dream found and lost. Wallace represented Democracy, not merely the semblance of lower case democracy, or smily faced politicians’ flag waving lip service to democracy, but the kind of democracy dreamed of by the founders, most notably Thomas Paine. His story, like Paine’s, is one of coming from common roots, only to bubble up to greatness through the thoughtful promotion of democratic ideals. The ideals that were built into the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. Ideals spoken of, but trounced upon by those who wish not to relinquish their dominance. Ideals spoken of by those who fear the fully realized practice of democracy.

The book digs into the crisis of the Great Depression. The implosion of the banking system caused by the mega-greed of wall street gamblers that sent waves of economic disaster around the world lasting until WWII. The combined devastation of the depression and the war put the prevention of the next Big One foremost in Wallace’s eyes. He never lost sight of the need for international cooperation. He never lost sight of the job of making democracy work. He never lost sight of, not just political democracy, but economic democracy as well.

This single mindedness of his was turned around to mutilate his political career. It was used against him in an ironically convoluted way. His goal of world peace was focused on establishing strong diplomatic ties of live and let live cooperation with the Soviets. This was in opposition to the hawks who would rather make an enemy of the Soviet Union in order to grow the “military industrial complex” that republican president Eisenhower, later in the ’50s, warned was taking control of US foreign policy. The destabilization of US-Soviet relations paved the way for the nuclear arms race and the Cold War that last for over 40 years, bankrupting the USSR, and costing billions of dollars, resources, and lives on both sides of the fence. As a result of his uncompromising stance, he was stamped with the label “communist,” then as now, a powerful denouncement. The authors left no stone unturned in trying to find evidence for this accusation. What they uncover is cause for concern. It’s the heart of the book.

Wallace’s story summons correspondences with Paine, a figure in history not without a good amount of criticism, refrigeration, and slamming. A patriot whose strong passions for democracy and equality put him at odds with his more rearward looking contemporaries. Although separated by almost 200 years, one can’t help seeing a few history-repeats-itself connections. Paine was not universally praise by his contemporaries, but wildly popular with the common citizen. Paine has been sidelined for his strong views, despite being a consummate proponent of democracy. Paine has been footnoted by historians, contrary to his indispensable contributions to the revolution that founded the United States. Like Paine, Wallace believed in the promise of America. For that he, too, has been footnoted even more so than Paine. He’s been forgotten, deliberately. He was a threat far greater than Theodor Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, or Franklin Roosevelt. He was despised for being on the side of, and believing in, a government “of the people, by the people, and for the people,” as stated in the Gettysburg Address by Abraham Lincoln, a republican. His detractors knew quite well that he wasn’t just mouthing the words, or playing for popular applause. He meant what he said. He was, for those reasons, a real threat to the security of reactionary superiority.

We have today a few Wallaces and Paines who have dedicated their lives to the democratization of the world of knowledge. Aaron Swartz, Edward Snowden, among others, who likewise have been accused of being traitors. They, like Wallace, are demonized by those who wish to keep knowledge and power from the commons.

The brightest shining similarity between Paine and Wallace is that both were dreamers—head in the clouds, castle in the sky, fairytale princess, rose colored glasses, utopian dreamers. They faced a flawed world, saw what it could be, and imagined how to get there. Time after time, dreamers get attacked by the unimaginative, by those who see the world and say, “It is what it is, always has been, always will be—y’ain’t gonna change human nature.” The defeatists see the ugly side of human nature; the dreamers think they can change it. The blindsided defeatists are flat wrong, and so are the misty eyed dreamers. What they’ve both missed is the other side of human nature. The side that doesn’t need changing—it just needs to be en-couraged.

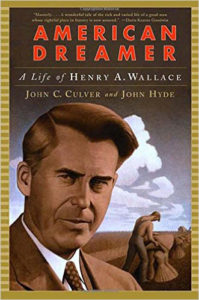

American Dreamer : A Life of Henry A. Wallace, John C. Culver & John Hyde, Norton, 2000

Also read [Where in the World is Thomas Paine?].

Watch [Killswitch : The Battle to Control the Internet]

Read [Requiem for a Dream]

![[art]by[odo]](https://artbyodo.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/cropped-Header.jpg)