— creative failure —

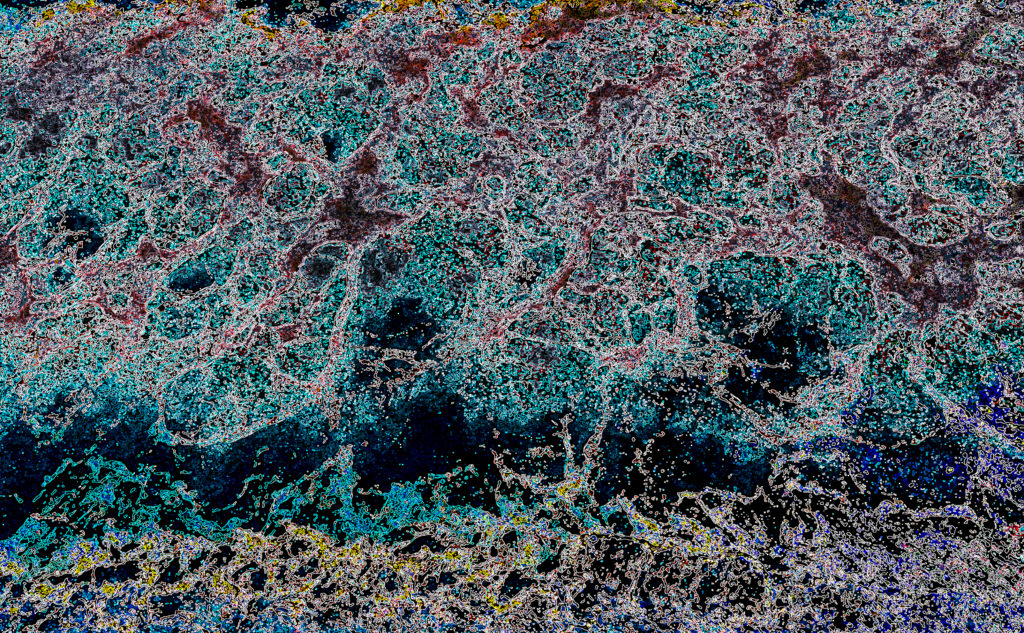

Computer art, or digital art, or computer generated art, or algorithmic art, or fractal art, or computer assisted, computer aided art, or datamoshing, or generative art, and there may be other names that I have yet to run across. Artists make use of every tool, any tool, they can get their hands on. Digital tools seem almost unlimited. They’ve opened up possibilities that a few decades ago were unimaginable. And I’m not turning back. I love silver-based photography, and I love digital. I hate silver-based photography, and I hate digital.

Let me explain. The chemistry of silver halide photography is magical. The unique beauty of silver and other chemical processes is unsurpassable. But chemical photography is hard. It takes years of practice and vast wells of knowledge to master a fraction of it. Unless you’ve worked everyday as a photographer you would have a difficult time appreciating the fear and frustration every professional lived with on a daily basis. You’d also not appreciate the satisfaction of hitting the mark when the results came out exactly as you had previsualized before pressing the shutter release. Digital changed all that.

Digital image capture is a near “what you see is what you get” medium. There’s no waiting for the film to be processed; there’s no guessing if you’ve got it. It’s right there on the screen before you press the button, and can be reviewed immediately if desired. But wait, there’s more. No only is the stress of getting a good expose relieved, there’s a myriad of calculations going on inside your digital camera (even the one in your mobile device) that’s focusing, adjusting color balance, compensating for camera motion, and expanding the dynamic range to help maintain detail in the highlights and shadows. These technical advancements are gobsmackingunfuckingbelievable. Film can’t do that. If you’ve never shot film, you haven’t a clue how drop-dead easy digital photography has gotten. I hate digital.

Enough of my love-hate affliction. What’s happened to photography is only a fraction of what digital has done to the production of art across the board. Painting, in particular, has been reeling since the invention of photography and still hasn’t recovered. New tools and technology keep taking the “hand” out of art production and putting it into the computer program (programmer). The old definition of artist was someone who was trained and skilled in producing something by hand, and art, consequently, the product of someone with a high degree of training and skills. It was an easy and obvious definition. There was no question. Perhaps a subtle difference existed between the artisan and the artist. The artist may have been considered someone who applied a greater degree of creativity to the medium. However, that appears to be a modern conception. The concept of art for art’s sake, and the contrast between art and an artisan’s beautiful, useful, decorative object—what we call craft today—is a recent distinction. In the past, there had never been a question of what is art, or who is an artist. It was a matter of refined knowledge and skill, not necessarily creativity, and certainly not originality.

Skills are easier to define than creativity. If modern art has become a creative process rather than a skill, then skill has no place in the definition of art or artist. This diminishment of the importance of skill has been growing for about a century. Art schools have deemphasized craftsmanship. They prize personal expression and originality. They’ve put the old ways to rest—aesthetics, mastery, virtuosity, are dead. Creativity is king.

Where is the creativity? Is the computer the artist? Is the programmer the artist? Is computer programming a skill or a creative process? Who’s the maker or creator when using digital tools? Were the Dadaists correct? Has art become only a conceptual process? Is everyone, anyone an artist?

But hold on, I started out talking about digital tools, moved on to skills, then creativity, then the conceptual/intellectual process. That’s getting too far off track and as confused as the current definition of art has become. There’s no easy way out of this, but I will circle back.

If it’s accepted that all available tools are fair game for artistic production, then nothing but the choice of what, when, and how much to apply those tools becomes the creative/artistic process. This means the control of these tools is the creative process, and mastery of these tools is the skill an artist learns in order to express his/her ideas.

That definition, I can live with. It was, for photography in the pre-digital era, the line in the sand that separated snapshots from creative/artistic imagery. Despite the mechanical production of the image by a lens, the photographer controlled every other variable via knowledge and skill. The photographer determined the outcome, not the camera. But then, also note that the artist is not the one who produced the lens, or manufactured the film, formulated the chemistry, etc. The photographer was in the position of director over these tools. Taken further, the photographer/artist might not even have been the person who actually controlled the camera, as with much of the work that came from the ateliers of most of the most famous painters. They didn’t put every brushstroke of paint on every painting. The artist, rather, was the master decision maker—”do this, not that”—and the person at the controls was merely a puppet. The master was/is the artist, not the technician who actually executes the work. That definition is harder to live with.

With the addition of digital tools taking more of the image making process out of the artist’s hands, there is mounting question of who is in control. The mechanical lens/camera means of making an image threatened painters by producing “perfect” pictures effortlessly. This mechanization also kept photography in the position of a second class medium of art. Digital further mechanizes and automates image making, and not only for photographers. It’s taken the reigns of most media. I’d argue it’s also taken decision making control away from the artist.

Technique alone is mechanics. Some are manual tools, such as brushes, chisels, lenses; some are automated, such as programed filters and algorithms. The art is in their application. The questions is, at what point does automation override creativity; at what point is the artist’s control over the tools lost? And the larger question, who is really at the controls, the technician, the operator, the director?

There are too many variables in this equation. There are too many other minds in the mix before, during, and after the creative process. There is no line in the sand. There is no “I” in the equation. Or at least, the “I” is a minor part that may be, in some cases at the center of the process, but more often, not in total control, or any control, and certainly cannot take all the credit. Top it off with the reliance on presets, filters, algorithms and other automated digital tools, the person at the buttons is hardly the creator of anything.

I have argued before that we’re all creative. Postmodernism and relativity argue that art is whatever the artist claims it is, regardless of who made it or how it was produced : no skill or creativity required. Relativity argues that anyone who claims to be an artist is one, regardless of knowledge or training : no talent required. And with digital tools, any gimp can spew out art. All you have to do is stumble on a “button.” We have wandered into a wonderland of weightless wazzle.

See the next post [This End Down].

See the previous [Really Fake].

![[art]by[odo]](https://artbyodo.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/cropped-Header.jpg)