neither follower nor liker be

Readers can tell how much I think of a book by how much I quote from it. With this book, I want to reprint the entire one-hundred-seventy-two pages. But I have to admit, this book was torturous. I didn’t need to read it. I already knew that advertising is about getting you to buy more than you need, more than you want, and more than is good for you. I already knew advertisers are desperate for eyeballs. I already knew that as conventional advertising is becoming more diluted, as broadcast media and print reach fewer numbers, and as the avarice of multinationals continues its insatiable acquisition of concentrated control, they keep looking for new ways to coerce the public into buying their products, and only their products. What I didn’t know is the extent of the newer, subtler, and underhanded means they’re using to rope in consumers (formerly known as customers). Worse yet, are the techniques being used for making you unpaid agents in the process of promoting their products.

This trend has become so pervasive that marketers are starting to proclaim that content marketing might soon become the only type of marketing left. Chances are, though, that you’ve never heard of content marketing, and that’s exactly the point.

Content marketing is producing infotainment that looks like ordinary newspaper columns, TV programming, magazine articles, as if it were from a trusted source. It’s about fooling you into thinking you’re read/viewing the producer’s honest views. It’s also about getting you to interact with the commercial content by feeding you “feel good” fluff. Something cute or amazing! that you’ll pass along to others. It’s sneaky.

We waste endless hours online reading this news clip or watching that video post, only to realize in the end that we haven’t interacted with anything of depth, and we can’t figure out why. Here’s the reason: marketing is not meant to engage our intellect; it is structured to elicit emotions. In pursuit of those emotions—typically awe or anger or amusement—we willingly continue to watch or read. After all, what’s one more cat video, especially when it’s so cute that you just have to share it with your friends? The problem is it’s like potato chips; you can never have just one.

Turning off the intellect turns off our defenses, shuts down our critical thinking. Not only have marketers tuned into our soft spots, they’re training our brains to tune into their content nets. The success of anti-social media is based on this. The deceit is that there is little truly social in sharing through these sites. What’s being shared is well camouflaged advertising. Given another thought, for something to be social, it requires a real time person to person interaction. No one ever called books social media. They communicate, but not socially. No one ever called letters or postcards social. Even the telephone, which is person to person communication in real time, has never been called a social medium, although it is.

While advertising sources create content with the express purpose of giving you something you want—advice, information, a coupon, a smile, a mindless break—news organizations are tasked with giving us information we need.

. . . it’s already the case that more and more advertising blends in seamlessly with noncommercial content, overwhelming the media environment and pushing real news further and further to the margins. There is a simple reason for this: if the goal is profit, legitimate content must take a back seat to clickbait and quizzes and entertaining cat videos, items that get us to spend time online in the hopes that we’ll purchase a product.

Priorities are in question. Recent centuries find most advanced countries pushing towards a well informed and educated public. It was viewed as necessary for democracy, and healthy for society. It’s the reason behind public libraries, public schools, investigative journalism, the scientific method, and public works, sanitary systems, potable water supplies, fire protection, parks, nature preserves, . . the list goes on. Not only that, an educated and accurately informed public is more civilized than an ignorant rabble. Yet, marketers seem to have found a powerful new means of pacifying the rabble and keep them blissfully ignorant. Feed them lots of vacuous entertainment. Distract them with fabricated controversy. Keep ’em fat ‘n’ happy with fast ‘n’ tasty (sugary/fatty/salty/lame/shallow/stupid). There’s nothing more compliant than a full stomach and an empty head. Don’t think for a minute that a college education means you are immune. We are all susceptible to fast and easy pleasure fixes.

Unfortunately, what we also come to believe is that amassing friends on [antisocial media] is ultimately about sharing with our compatriots. It is not: it is about creating an audience for advertisers. Our relationships, then, become means of facilitating market transactions, or in the parlance of the market: they have been monetized.

You’ve been sharing with the multinational, not your friends. You’ve been working for them without getting paid a penny. You’ve been bamboozled by cute and amazing. You are their minion.

But what if you don’t know that a blog post has a marketer behind it, or that the celebrity tweeting about a lip balm was paid $20,000 for those 140 characters, or that a newspaper article was sponsored by an online streaming video service, or that a documentary you watched on [Big Nature Channel] was paid for by an oil company? If you knew it was advertising chances are you’d speed by it the same way you zap past a commercial on your DVR or dump your junk mail in the [trash] bin. Or if you did watch it, aware of the content’s sponsorship, you might approach it with a more critical or cynical eye—something companies do not want you to do.

Of course not, the goal today is not to pull up the bottom of society, or to improve the average, or to make a better functioning civilization. There seems to be nothing left to do but make money and hold the reins of power. And it’s so easy, just dangle a few tantalizing visual carrots in front of them.

If you’re an astute reader, you may be questioning this site. If you’re a regular, I needn’t explain nor justify.

Note : In an effort to keep mention of specific corporations out of this review (I’ve let two small ones go), and to insure that there is no hidden commercial agenda, I have redacted company names from these quotations. I feel no need to give them more free publicity, anyway, it doesn’t matter which ones they are, the names could be interchangeable.

[Big Pet Food] is able to engage with Laura and other consumers like her because they scan the Internet in real time looking for mentions of cats and dogs—an activity known as social listening—and determine how they can insert themselves into the conversation. Did Laura buy [Big Pet Food]? I don’t know. But she did become a brand ambassador in response to some brief corporate attention. And it didn’t feel like marketing, either to her or to the followers with whom she shared the [mindless post on an antisocial medium].

The creep factor of stories such as this one gives me chills. “Social listening.” “Insert themselves in the conversation.” Does this make you want to delete everything you’ve uploaded to antisocial media sites? I did years ago, soon after I got a “Happy Birthday” from someone I hardly knew, but “friended” on one of those sites. Then I read the Terms of Service. I didn’t get past the second page before I said to myself, “I’m outta here. I will NOT give you my content. I do NOT agree.”

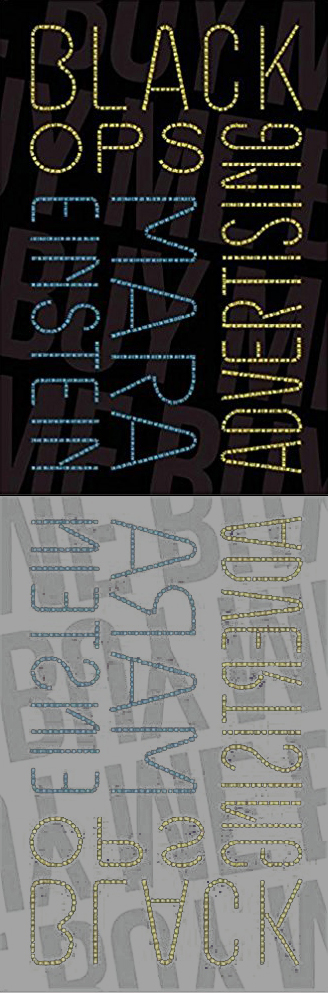

While content marketing has become pervasive, it is part of a larger overall trend of the muddying of advertising and editorial: that is, black ops advertising.

The correlation to combat is purposeful. Marketing has always been framed as contentious and militaristic. Marketers have objectives that they need to achieve: they use a variety of sophisticated strategies to achieve those objectives, and then they operationalize those strategies through the use of tactics. And of course, consumers—that is, you and I—are targets.

More questions must be asked. If advertising is innocent and harmless, why do these marketers work so hard at strategies? Why do they use tactics? If someone makes a good product that people need and want, the customer will come to them. There’s no need to lasso customers. Just as a reminder, customers no longer matter, only consumers. It’s all about buy, buy, and buy some more.

Branding, quite simply, is the use of a recognizable logo, a tagline (though not always), and a mythology. A sneaker isn’t a running shoe; it is a [Big Sneaker Name] and the athletic excellence that embodies. [Big Sappy Entertainment] isn’t a theme park; it is magic. [Big Unhealthy Drink] isn’t a sugary carbonated beverage; it is happiness.

Wow! It is true. We no longer buy a good shoe, we buy into the image of that shoe. We wouldn’t buy an artificial and nutritionally worthless beverage, we buy a happy sugar fix. Which you could get from a fresh piece of ripe fruit that includes a multitude of micronutrients and fiber and costs less.

At this point, I’d only read to page 60, it was already clear, I really didn’t need to read more. It was screaming bright and clear; advertising is the second worst human invention ever, and so close a second that it could be tied with first. The author, Mara Einstein, goes on to cover consumer generated marketing. Talk about head exploding incredulity. Why, how would anyone start, operate, maintain, and pay for a fan-site worshipping a commercial product? And more incredulous are the blind sheep who follow it. I can’t get my head around what the fan gets out of it. I have an inkling that it’s the vicarious external validation. By supporting a ‘winner’ it shows that “I’m a wiener too.” It’s part of what’s behind all sorts of crazes, fads, and followings. Since “I don’t have enough confidence in my own opinion, views, thoughts,” that inner need will be filled with an outside source to bolster one’s self image, whether that source is direct, winning a prize; or indirect, being a fan of a winner.

Technology also helps propel disclosure and sharing. Most people do not effectively use privacy settings, and so they overshare without even knowing it. [Big Anti-social Site] continually changes its privacy settings to test how far they can go with making information visible by default.

There’s another good reason to delete one’s anti-social media accounts. I wonder, how many of the 1.3 billion users would be users if they read the TOS? How many would pay a subscription fee? In case you don’t know, that “free” site could make more money by charging a meager $20 per year than they do from advertisers. That’s worth a second read. (They make only pennies per user per month.) But ask yourself again, “Would I pay for this? How much?” There’s a reason it’s “free.”

…the [Big Struggling Newspaper], readers spend similar amounts of time with sponsored posts (that is, advertising) as they spend with legitimate news stories. Some “paid posts” have even outpaced news stories. The question is, though: did readers know they were “paid posts”? We just don’t know.

Paid posts, paid content, made to look and read exactly like the publication’s real editorial content, is usually marked, subtly. It’s easy to overlook and not realize that you are not reading objective journalism, but rather, heavily slanted sponsor paid-for content. It’s sneaky. It’s dishonest. It’s abhorrent. Although, “do readers know they were ‘paid posts’?” is not a bad question; it’s the wrong question. It almost doesn’t matter if readers know or not, the problem is advertising is getting nearly equal attention as substantive editorial content. That’s disturbing.

Humorous, mindless, irreverent content makes up the bulk of what appears on [BF]. That and cats. This lightweight content is used to attract the “bored at work network,” Millennials who are at their desk during lunch looking for a lift and a laugh that they can share with friends.

“Pigs get fat; hogs get slaughtered,” as the saying goes. Millennials are the pigs being fattened up for the slaughter. There’s a pattern beginning to appear. Millions of people are bored, dissatisfied, unfulfilled by their meaningless corporate jobs. Jobs that are mindless and irrelevant as much as the “content” they watch and “share,” and as mindless and irrelevant as advertising. Perhaps our problems are more profound than surreptitious advertising. We may be constructing an entire society based on empty commercial pursuits that leave us longing for something more, something real.

The [Big Online Publisher] stirred up commotion in early 2015 when it pulled an article about [Big Soap] products that poked fun at the brand. [Big Soap] is owned by [Big Multinational], which is a major advertiser on the site. Gawker called them out on the deletion, saying, “[The reporter’s] post was legitimate criticism of an exploitative marketing campaign underwritten by one of the largest and most powerful advertisers on the planet. In other words, the reason her post was necessary—in a way so many [BF] posts are not—seems to be the very reason [BOP] deleted it.” News director Ben Smith did a mea culpa on [Big Useless Site] and the article was restored. The reporter, however, left the company and did not return.

The irony of this is that bad publicity is good. The buzz of bad publicity is how the current president of the most powerful country in the world got elected. The press was all over him day and night. (Who ran against him?) The doubled down irony is that controversy over controversy is more buzz, and the beauty of buzzing over buzz is its ultimate meaninglessness–a distraction from the real issues. Ultimately the marketer’s goal, and the media’s goal, is to make an emotional connection. Appealing to the mind doesn’t get people excited. Real in depth, intellectual engagement is slow and methodical. Instead of improving the minds of their readers, the aim is to anesthetize their intelligence and stimulate their irrational emotions to loosen them up to buy, buy, and buy some more.

If insinuated commercial messages weren’t enough, there is custom content that only hints at who the sponsor could be. From an advertising standpoint it seems superficially illogical. But here’s the most insidious aspect. The stealth sponsor isn’t looking for direct sales, their goal is propaganda–emotionally influencing minds and opinions. This is Big Brother. Yes, Ronny was right, government isn’t the answer, it’s the problem. The problem is government has relinquished its responsibility to protect the people. Let BIG BROTHER corporations take control—it’s good for the economy. Not my economy, nor yours.

As more and more smaller companies get eaten up by the same few monster multinationals, there are fewer and fewer voices to be heard. The internet has provided everyone with a voice, but as these Big Brothers steal more of the show, as they drown out any little voice that could interfere or disagree or wake up the average person from their cute kitty-kat videos and mind numbing diversions, the hopes and promises of a verdant coequal world wide web has turned into a shriveled monotonous desert. There will be no shaking people out of their submissive trance. Real free choice and diversity is bring desiccated.

Publishers and advertisers claim they are giving us what we want. Einstein doesn’t agree, neither do I. We don’t want one sided propaganda. We don’t need to be force-fed extreme opposite opinions, presented under the guise of fair & balanced, that are invariably setup to make one side look ridiculous. This is more than a crisis in advertising, it’s a full-on media crisis.

More and more content being produced means more advertiser-provided information at various levels of obscurity. Here’s why this might be an issue. According to the company’s Mission 2020 agenda, [Big Sugary Drink] has the goal to be water neutral. The website has presented a number of pieces about reducing water usage, which is not only good promotion for them, but which achieves search engine optimization (SEO)—that is, their content appears organically at the top of the [Big Engine] search. At the same time that the company was promoting conservation one of its plants in India had to be shut down because its overuse of water was affecting local farmers. This is no small issue, and water availability is becoming an increasingly important problem around the globe. Yet if [Big Sugary Drink] can keep churning out the positive content, it forces the reality of its role in water overuse further and further down the search.

Once more, this highlights how the truth is being manipulated. By talking about water conservation, promoting water conservation (you conserve), and presenting itself as being a leader in the field of green, it obfuscates its own diametrically opposite behavior. Corporate creeds today consistently pretend to “be good citizens,” or “do no harm,” while completely ignoring them in practice. As the saying goes, “Actions speak louder than words,” or in the case of these content sites, louder than pictures.

Furthermore, Einstein points out how big brands are taking over the media. “‘Large brands like [Big Conglomerate] and [Big Multinational] are publishing more content per week now than [Big Publisher] magazine did in its heyday.’ Multiply that by hundreds or even thousands of companies and you can begin to see how editorial content doesn’t stand a chance.” This poses more questions. What does it means to have a free press? Do we continue to have a free press? When will we stand up to this violation of democratic principles? Of course, we can’t stand up if we don’t know what’s really going on behind the curtain. As I mentioned in the first paragraph, the whole book, every page, has important curtain shredding information neatly consolidated between the covers.

One more final snippet from the book. (And I haven’t even touched on chapters six and seven.)

Research from ad buying and video marketing platform Pixability found in 2014 that “the top 100 global brands have nearly 1,400 YouTube channels.” This constitutes more than 360,000 videos, with more than 19 billion views, representing an increase of 39 percent in just one year.

Hard hitting marketers are deluging the web with their content, overwhelming any potential for the egalitarian high hopes of digital media, or more critically, any semblance of honesty and accountability. Page after page of jaw dropping revelations of how BigBro multinationals are manipulating us psychologically and emotionally to become our “friend” goes from creepy to disgusting to alarming. Getting us to self identify with their product, if you think about it, is bizarre. This is what following and sharing really means. What I’ve pulled from the book is only a fraction of her startling report. Some of the most gut wrenching parts are the quotations she got from interviews with ad executives. The peculiar rationalizations and self contradictory statements are bewildering.

Black Ops Advertising nails it : Advertising is evil. That may sound hyperbolic. It would be if advertising told us only what we need to know : Who/What. In the beginning that was the purpose of publicity, to let us know who did what. From simply letting the public know what’s available, and leaving it to the customer to choose as one needs, advertising has been twisted into the seller telling you what you want, when, where, and how much you want it. It’s been weaponized against other sellers, who may be equally good, or likely better, so that you won’t give them a second thought. It’s become a high powered laser aimed at the consumer without regard to health or welfare of the individual, or the public, or the environment. Op out.

Black Ops Advertising, Mara Einstein, OR Books, 2016

“Arguing that you don’t care about the right to privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different than saying you don’t care about free speech because you have nothing to say.” — Edward Snowden

also read [Dubble Bubble]

![[art]by[odo]](https://artbyodo.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/cropped-Header.jpg)